Age: 45

Location: Florida

When did you discover anime? (Note: Not long ago, I wrote an essay that contains many of the answers to these questions. I’ll be quoting parts of that essay here as my response.)

For a while, I didn’t even know the name of the first anime series I ever watched. I didn’t even know it was “anime”. It was merely this curious-looking TV show that appeared in one of the leased-time programming blocks on a UHF station that reached my house in northern New Jersey in the early 1980s. Most animated shows were about cartoon animals beating each other into bloodless submission; this one was about a boy with a shaved head living in Japan’s distant past.

The show was called Ikkyu-san, and its sheer oddity (at the time, anyway) made me go back to the leased-time programming block to see what else might turn up. Sure enough, later on, other shows also from Japan appeared: Space Battleship Yamato, Galaxy Express 999. All of them, including Ikkyu-san, aired with English subtitles. (Between those and the foreign films that aired on PBS, the idea of reading my movies was something I got comfortable with at an early age.) But again, the idea that I was watching something special called “anime” hadn’t entered my mind yet.

In a way, I got into anime backwards. The idea of Japan being a place of interesting things had lodged in my mind early enough that at the tender age of ten, I found myself spending one of my last dollars on a Yukio Mishima novel that proved too tough for me to plow through at the time. A little later came Akira Kurosawa’s Ran, just then in theaters for the first time, and the impact of that sent me scurrying back to the library with a whole passel of names to research: Kurosawa himself, composer Toru Takemitsu, actor Tatsuya Nakadai. The books I unearthed about Japan’s live-action film industry dated from too far back and were too narrow in scope to say anything substantive about animation. There had to be more.

It wasn’t until six years later, when Akira got fairly dropped on my head by a friend, that I was reminded in a full-blown way that yes, Japan did animation too. Boy, did they ever. With far more ambition and enormity of purpose than most anything in this side of the Pacific, too, from what I’d seen. That touched off the second phase of my “Japan thing”, punctuated not only by buying up anime itself, but back issues of the late lamented Mangajin and remaindered copies of Anime UK. A whole culture of others existed who were as curious as I was.

What appealed to you about anime when you first discovered it? Some of it was the thrill of discovering something that, at the time, seemed like completely undiscovered territory. It wasn’t until I was into my college years that I realized the material in question had a specific label. That made it all the more mysterious, and for that reason all the more inviting.

The other thing that appealed to me was how it presented the absolute flipside, as it were, of everything I’d come to know about Japan through its literature and its cinema. Much of that material had been staid, sober, straight-laced. This stuff was anything but. The contrast between the two made me feel like I had been given a privileged glimpse at Japan—at least until it became a relatively mainstream phenomenon in the West.

What would you say was the most popular anime at the time? At the time of my first exposure, there wasn’t one, as anime hadn’t yet become a thing of any kind in the U.S.

What was it like to be a part of anime fandom at the time?

As I was to later understand it, there was essentially no fandom in the U.S. worth speaking of at the time. There were people scattered here and there who had stumbled across this stuff and were spreading enthusiasm about it essentially by word of mouth between peers. But no fandom as we currently know it.

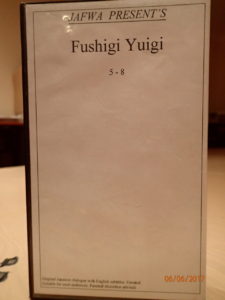

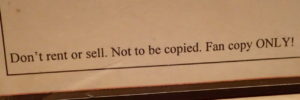

Where and how did you access anime? Were you able to buy it at stores? Most access was by way of whatever was available at the local video rental store. Very occasionally, I picked up an import LaserDisc (albeit with no English subs); occasionally, bootlegs as well. Sometimes I’d go to the Tower Records Bargain Annex in downtown NYC and pick up cheap stuff from the cut-out bin. (I also found many back issues of “Animage” there, which only fueled my curiosity all the more.) But it wasn’t until DVD came along—and until I had more disposable income generally!—that I could really begin to satisfy my curiosity properly.

In such an early time for fandom, what did your family and friends think of your interest in anime? When they did know about it, they understood it mostly as an adjunct to my existing interest in Japan. That impression was doubled when I started buying the now-defunct magazine “Mangajin”, which I wrote briefly for just before they went bust. My other friends who were fans saw it as being essentially the same kind of thing as being a fan of, say, European comics/BD: a niche taste.

Was the Internet a part of fandom at the time? I had to wait until the Internet came along before I became fully aware of the breadth and depth of anime fandom. The fans had been out there waiting all along for something like that to help them find each other. Before that, there were U.S. and U.K.-based publications like “Anime UK”, and publishers like Dark Horse Comics, but they were very few and far between. My only connections with other fans until the Internet really took off was almost entirely by accident.

What kind of accident? Most of how I bumped into other anime/manga fans during that time period was by way of other things—role-playing games, for instance, or meetings at conventions that didn’t really have an anime theme track. I was always surprised by the mere fact that they knew about anime or manga at all. They also almost always had some novel facet of it to share that I’d never been aware of before, again because access to any information at all about such stuff was so hard to come by.

How did you first get Internet and discover over fans that way? I was an early adopter. In the early ’90s, I was an avid dial-up BBS user, and from there I gravitated to online services that were the precursor of modern Internet connectivity. A key one was CompuServe, which had SIGs (Special Interest Groups) that covered a great many subjects. As weird as this sounds, I never thought to look specifically for anything anime/manga related in such SIGs, in big part because I always believed the whole thing was still too obscure to merit that kind of documentation! Eventually, when my CompuServe account became an actual Internet account (by way of another early dial-up provider), I bumped into the first web sites put up by anime fans.

Do you remember your first convention? The first convention, period, that I attended was not specifically anime-themed—it was a general SF/fantasy con with some minor anime track programming. The folks in the anime track were a lot more welcoming than those in the general SF track. Later, when I attended my first general anime con, I found that feeling to have been spot-on.

Tell me how you started writing about anime for About.com. It happened twice, actually! I started back in the late ’90s, when they first appeared under the moniker “The Mining Company” (as in, mining the web for useful information), and managed their anime subsite for several months. I left mainly because I was having trouble juggling the workload, and because I was able to make more money doing freelance work in other venues.

Some years later, in 2010, I circled back and saw they needed an anime guide once again, re-applied, and was accepted. I kept that position for three years, but I didn’t like the format constraints imposed on my work, struggled with their toolset, and grew annoyed with the general lack of guidance. After three years of declining traffic they elected not to renew my contract, and I didn’t shed any tears. One month later I launched Ganriki.org.

Tell me about your anime-inspired novels, and anime-inspired writing in general. In the spirit of this project, how did that start? The first project I did that really fit in that category was probably my 2007 novel Summerworld, which was as much an outgrowth of my general studies of Japan as it was an attempt to do something that had an anime flavor or theme to it. The same went for Tokyo Inferno, which stemmed from me wanting to write something that was set in the Taishō Era, and that had a strong horror/supernatural flavor to it. A third such project in that vein was The Four-Day Weekend, a sort-of love letter to the fandom/convention scene, although that was more about the culture around anime/manga (and the ways people create substitute families through appreciation for such things) than the subject itself.

After that, though, I made a conscious effort to move further way from doing explicit homage to anime/manga in my work. (Another book from this period that did have such things in it, The Underground Sun, remains unfinished, and I don’t know if I’ll ever complete it at this rate.) But a lot of what I took away from the experience of creating those books continues to influence the work I do now, even if my current work isn’t explicitly influenced by anime/manga

What I wanted to keep was not any one particular set of elements or aesthetic sensibilities—it didn’t have to be set in Japan, or employ tropes familiar to anime fans, or what have you. Rather it was about the narrative energy, the thematic fearlessness, the thrill of encountering something unfamiliar but at the same time immediate and accessible. Watching and reading anime and manga sparked those feelings in me, and I wanted to find any way I could to create them on my own for my audience, in a way that only I could.

For you personally, what’s the biggest difference between being an anime fan then and now? The biggest thing I can think of is the ease of access and entry. It used to be appallingly difficult to learn *anything* at all about anime or manga; now, it’s more a question of which of a dozen different competing venues to choose from and be flooded with.

But that also means there’s that much less curation going on. Once, a given label could only license a handful of properties for U.S. distribution, and so they had to pick wisely. Now, you have access to every show airing in Japan within hours of it debuting over there. That means more of the burden of making choices falls on your shoulders. And let’s face it—a lot of what was released back in the day wasn’t “classic”; it was crap, too, and some of it really only got elevated to the level of classic because there was so little of the stuff available in the first place that you tended to latch onto whatever was offered.

There’s so much anime and manga out there right now that it’s difficult for people just coming in the door to know where to start or how to proceed. Sometimes they walk in, look around, feel lost, and walk right back out again. The usual tactics of marketing for a given demographic only go so far, especially as people find that good properties defy demographic boundaries. (I can’t *only* recommend Revolutionary Girl Utena or Princess Jellyfish to women, but I know they will find them especially heartening.) So the biggest difference between then and now is, where before we had to learn how not to die of thirst, now we have to learn how now to drown.

Serdar can be reached on Twitter and his blog.

To this day I have watched 274 different TV anime and am an avid cosplayer. I have gotten many other people into the medium and am even learning Japanese with great enthusiasm. Most strikingly, it has helped me deal with the treatment-resistant depression that has been slowly taking all positive feelings away from me over the years. Stories like NGE,

To this day I have watched 274 different TV anime and am an avid cosplayer. I have gotten many other people into the medium and am even learning Japanese with great enthusiasm. Most strikingly, it has helped me deal with the treatment-resistant depression that has been slowly taking all positive feelings away from me over the years. Stories like NGE,